This post was originally published HERE on Toy Adams's Advent Blog, Imagining Jesus.

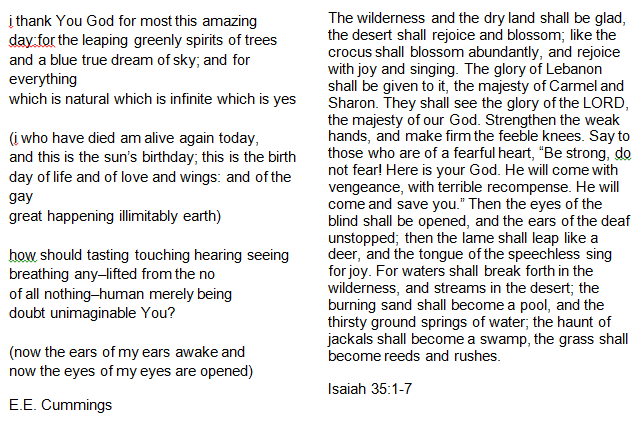

Advent is the season of anticipating Yes. It’s the season of the breaking-in of the infinite, and the season of the eternal embrace of the natural. The season of the perhaps-possible impossible. The Event of Emmanuel—God with us, God in us, God as us.

God’s answer to the no of humanity’s un-love is the yes of childbirth, in all its pain and blood and promise. God becomes a human merely being—tasting touching hearing seeing breathing—and perhaps is always still becoming human, as we also are.

During advent, we anticipate the sun’s birthday at the start of winter. And, oh, how long the winters of our lives can be. Sometimes they last for years. And still, we wait for the promise of sun, for those leaping greenly spirits to re-emerge, to become alive again after we have died.

Perhaps this is a hope against hope, for a blue true dream of sky is not enough to assuage the acute and actual pang of sorrow and suffering. But knowing that God is merely being right alongside us—wailing in a manger, wailing on a cross—means that while the depths of human suffering are illimitable, so too are the gay great happenings. Our ears may awake to the no of all nothing, but our eyes may be opened to life and love and wings.